Barcelona in 1900

When Park Güell began to be built in 1900, Barcelona was a modern and cosmopolitan metropolis whose economy was based on the strength of its industry and which had over half a million inhabitants. Its walls had been knocked down nearly half a century earlier and the new city, the Eixample planned by engineer Ildefons Cerdà, had grown spectacularly from 1860 onwards, in what was the largest 19th century city development project in Europe.

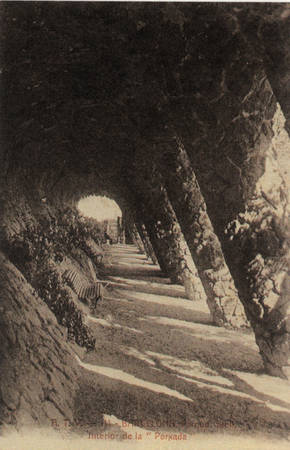

Parc Güell, "Interior of the Laundry Room Portico",

© Collection Ernesto Boix. Cercle Cartòfil de Catalunya

Ildefons Cerdà had made a thorough study of the difficulties of modern growth within the walled Barcelona and the impact of technological changes, especially the railway. The plan for his Pla d’Eixample proposal increased the area of Barcelona tenfold, as the result of a practical vision of the city. Cerdà conceived the plan as a flexible instrument undertaken with a reformist spirit in order to foster the formation of a modern city that would be more effective, healthier and fairer.

Barcelona expanded very rapidly throughout the second half of the 19th century, with the Eixample spreading out over the plain. Its central area began to take shape as a large bourgeois centre, while development also advanced along its flanks, in the direction of the old manufacturing areas on the plain, with a more popular and industrial nature

The Universal Exhibition of 1888 showed Europe and the world the dynamic thrust of Barcelona, capital of a Catalan nation being reborn, and boosted the quest for a new artistic language and idiom of urban representation. That explained the success of the Modernisme movement, very much in evidence at the heart of the Eixample, and the work of an architect as singular as Antoni Gaudí.

Modernisme and Catalan Culture

The Modernisme movement is akin to the movements elsewhere known as Sezession, Liberty, Jugendstil or art nouveau. Unlike those movements, however, Modernisme had an ambition that was not limited to aesthetic renewal: it was the expression of a desire for the modernisation and cultural resurgence of Catalonia, fed by the dynamism of its capital, Barcelona.This was why Modernisme went beyond architecture and the plastic arts, also playing an important role in language, literature and music.

While the salient feature of art nouveau, under its various modalities and denominations, was a wish to create an international architectural style that reflected the cosmopolitan fin-de-siècle culture, the Catalan movement sought a new synthesis between tradition and the most radical modernity.

In Catalonia the cosmopolitan spirit of art nouveau came out as a general idea of modernity rooted in an ambition to project the country into the future based on the foundation of absorbing its deepest cultural roots.

Detail of Park Güell. With the Hypostyle Room in the background

Barcelona, the city of Modernisme

From the 1860s, the construction of the Eixample gave Barcelona’s architects many professional openings for expression, endowing the city with one of the continent’s richest and fullest repertoires. The first attempts at Modernisme were brought into its wide spectrum of historicist and eclectic architecture at the end of the century.

Car fair to raise money for the Asil de Santa Llúcia shelter, attended by the Spanish princesses.

© Frederic Ballell. Arxiu Fotogràfic de Barcelona

At the time when the forms of art nouveauwere beginning to spread through Brussels and Glasgow, amidst the widespread domination of historicist and eclectic architecture all over Europe, Barcelona was embarking on an equally original development. From the 1888 Exhibition, the most innovative architects began to recover former construction techniques such as the Catalan vault (or timbrel vault) and old craft styles, while at the same time taking an interest in the expressive potential of iron. Many modernist architects, such as Antoni Gaudí, Lluís Domènech i Montaner and Josep Puig i Cadafalch, began their careers in this setting.

When art nouveau finally triumphed at the International Exhibition in Paris in 1900, and forms derived from nature became a new model from both the structural and ornamental viewpoints, in Barcelona this notion fell on fertile ground. A large group of architects, among them Enric Sagnier, who was enjoying great success in the city at that time, and Jeroni Granell i Manresa, soon incorporated naturalist decorations, though remaining in the sphere of eclectic architecture. On the other hand, the most significant architects within Modernisme, such as Domènech i Montaner and Gaudí, went very much further in their original interpretation of art nouveau, based on the paradox of having to be modern without renouncing tradition.

Detail of Park Güell’s main entrance gate